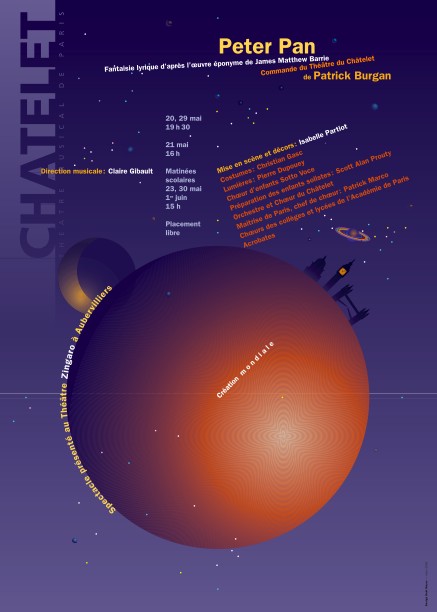

Peter Pan or the real story of Wendy Moira Angela Darling

Lyrical Fantasy. Libretto by the composer from the James-Matthew Barrie’s tale

(2004-2006)

Duration : ca. 2h

Commission of Théâtre du Châtelet.

World premiere on may and june 2006 at the Théâtre Zingaro in Paris (Aubervilliers)

Marie-Christine Barrault, Gaële Le Roi, Marc Barrard, François Piolino, Erik Freulon, Maîtrise de Paris, soloists of Children’s choir Sotto voce, orchestra and choirs of Théâtre du Châtelet

Musical director : Claire Gibault

Direction, stage design and “Prop-costumes” designer : Isabelle Partiot

Costume designer : Christian Gasc Light designer : Pierre Dupouey

Album 2CD-DVD (Klarthe Records) – More – Label website – Listen CD

“Arrival to Neverland” :

“The parade” :

“I remember…” :

“Wendy tells her story” :

“Tinker bell’s death” :

NOTE ABOUT THE WORK

Note of intent from the composer A reading of Peter Pan, by Sylviane Falcinelli List of caracters and instruments Scenic structure and connections “spoken-sung” Synopsis Pictures of Théâtre du Châtelet’s production Interview du compositeur Note d’Isabelle Partiot-Pieri (Mise en scène,décors, costumes accessoirisés) World premiere’s casting and specifications of the Stage director about her options

Note of intent from the composer

(Back to top)

The story of Peter Pan – best known through the simplistic reading of Walt Disney cartoon – is revealed in the original tale by JM Barrie, an amazing parable about life and death.

The Opera strengthens the abyss and the game on the eternal return, including the premature loss of Wendy’s brother which is none other than Peter, joined by her in the afterlife: the Neverland.

Three worlds alternate on stage with relatively cinematic techniques (flashbacks, fades, abrupt transitions).

The first one, central axis, brings together two actresses: Wendy, now a grandmother, tells her story to her granddaughter Lucy, with all the distortions and contradictions maybe less due to her age than her compulsive lying.

The second and third worlds are the illustration of her words, the living pictures of her memory: the bedroom of her childhood, where the voices are spoken (but this time wedged rhythmically with the orchestra) over an orchestral support; Neverland, the 3rd world, is entirely sung.

The presence of music is thus proportional to the distance taken with reality, since the actresses just talk (here and now), the soloists talk over the orchestra (the memory), soloists and choirs sing when everything is no more than music (the dream).

Mermaids, fairies, pirates, Indians, wild animals, domestic disputes, loss of children, longing look at his past, etc. From reflection on the eternal childhood (the only life can offer aging) to the most spectacular battles, could this opera – as the story of JM Barrie – remain open to all reading levels.

A reading of Peter Pan, by Sylviane Falcinelli

Those who have the privilege to frequent Patrick Burgan must know his voice with passionate and sunny inflections, his eyes kindling to the slightest spark of enthusiasm, his sense of wonder: In fact, a tireless child has survived in the depths of his heart. However, his reflection, his cultural and spiritual scope lead him to high spheres and we find the many facets of his personality in the various strata of the readings to which his Peter Pan lends itself. Indeed, whether it comes to setting the poems to music (and this in the five languages in which he is fluent) or great Latin texts, this lover of literature is imbued with these writings to the point of delivering a true exegesis, which structures in a determinant way the complexity of the musical discourse. His imagination needs this relationship of intense love for literature and his acuity obliges us to re-read the classics of which we were unable to weigh up every word. It would be deeply wrong to thinking that this time he has illustrated a famous children’s story. He has re-read (as he tend to do) a tale which, like all tales, conveys universal values well: He has found (sometimes painful) questions on how we grow up betraying our childhood dreams, on the relation with memory, on the wonderful world of imagination where every artist lives in one way or another, on the difficult transition from dream to reality; he has detected in James Matthew Barrie’s Peter Pan the almost psychoanalytic repercussions of a painful experience (mourning the writer’s brother, who died at the age of thirteen) and incorporated them in his reconstruction of the text. The show can marvel young audiences; the libretto offers a dialogued narration open to all ages; the music arouses unexpected dimensions connected with a metaphysics of childhood, birth, death, which the composer has been pursuing for years.

List of caracters and instruments

(Back to top)

Caracters

Actors

Granny Wendy (Wendy old) : speaking role

Lucy, her grand-daughter (ca.10 years old) : speaking role

Soloist singers

Peter Pan, young boy (ca. 12 years old) : child voice

Wendy, young girl (ca. 15 years old) : soprano

Mrs Darling – Tin-Tam (Tinker bell) : soprano coloratura

Mr Darling – Captain Hook : bass-baritone

Nanita, nanny – Simoun, pirate : light tenor

Guignard, lost boy (ca. 12 y.o) : child voice

Zigomo, lost boy (ca. 12 y.o) : child voice

Frisé, lost boy (ca. 12 y.o) : child voice

Flocon, lost boy (ca. 12 y.o) : child voice

Teigne, pirate – Indian chief : bass

Lys Tigré, indian chief’s daughter (ca. 16 y.o) : mezzo-soprano

Choirs

Pirates : male choir

Mermaids : female choir

Indian warriors : male choir

Indian women : female choir

Indian kids : children’s choir

Boys (the lost children) : children’s choir

Fairies : children’s choir and/or female choir

Wildcats, snakes, wolves, crocodile : children’s choir

Orchestra

(2/2/2/2 – 2/2/2/1 – 3 perc./ Piano-Celesta-Digital keyboard/ Harp/ Strings)

Flute

Piccolo

Oboe

English horn*

Clarinet in B*

Bass clarinet in B* (with D# low)

Fagott

Contrafagott

2 french horns*

2 trumpets

2 trombones

Tuba

Perc. I : 2 timbals (Do1 à Si1; Do2 à Ré3), Triangle, Grelots, Lge cymbal on foot, Lge cymbale to put on timb., Enclume, Métal chimes, Glockenspiel

Perc. II : Marimba, Glockenspiel with pedal, Tubular bells (Eb3 to C#4), Triangle, crash cymbals, 2 cymbals (méd., low), rivet cymbal, Tam-tam very large, Claves, Tamborin, Guiro, Washboard, 4 toms (high, méd, low, very low), Bass drum

Perc. III : Vibraphone, Tubular bell (E3), Métal chimes, crash cymbals, 2 cymbals (high, low), 3 tam-tams (high, méd, low), 2 wood-blocks, 2 temple blocks, Whip, 2 maracas, snare drum, 2 toms (méd.,very low), 2 bongos, Bass drum, Lion’s roar, Eoliphon

Piano – Celesta – Digital keyboard

Harp

Violins I

Violas

Cellos

Double basses (5 strings)

Scenic structure and connections “spoken-sung”

Scenic structure

Three worlds alternate on stage and are activated by lightings ; their interventions are sometimes simultaneous, most of the time successive.

1st world : Old Wendy tells her adventures to her grand-daughter Lucy (global duration : ca. 11 mn).

2d world : Young Wendy’s bedroom ; in the background, the door of her parent’s bedroom (global duration : ca. 21 mn).

3rd world : the Neverland ; here are the choirs (lost children, pirates, indians, wild beasts, mermaids, fairies…) ; here stand most part of the action (global duration : ca. 90 mn).

The 1st world is the central axis where Granny Wendy tells her story : she is the narrator of this tale.

2d and 3rd worlds are the illustrations of her words ; the alive images of her memory.

Connexions « spoken-sung »

In a general way, spoken is reserved for the real action ; sung for the imaginary one.

Therefore, 1st world is entirely spoken (vocal and orchestra may occure during transitions, when the narrative is embodied on the stage).

In the 2d world, all voices are spoken mais but orchestra is omnipresent. Vocal sometimes occures when the imaginary world is present or even just evoked.

3rd world is entirely sung (soloists, choirs) ; the action is clearly set out by the numerous interventions of the narrator Granny Wendy (1st world).

Synopsis

Three worlds alternate on stage. The first one, central axis, brings together two actresses: Wendy, now a grandmother, tells her story to her granddaughter Lucy, with all the distortions and contradictions maybe less due to her age than her compulsive lying. The second and third worlds are the illustration of her words, the living pictures of her memory: The bedroom of her childhood, where the voices are spoken over an orchestral support; Neverland is entirely sung. The presence of music is thus proportional to the distance taken with reality, since the actresses talk (here and now), the soloists talk over the orchestra (the memory), soloists and choirs sing when everything is no more than music (the dream).

Scene 1a (2nd world) Wendy’s bedroom

A violent argument between Mr and Mrs Darling is heard behind the stage.

Wendy is sitting on her bed, covering her ears. When the argument dies down, she takes a kind of black material (Peter Pan’s shadow) out from under her pillow. More raised voices; Wendy puts the shadow back.

Scene 1b (2nd world) “Oh, my dear! Your father!”

Mrs Darling enters the bedroom and confides in her daughter; nothing is like it was before. She is referring to the elder brother who died several years’ ago; he would have been thirteen today. “Like Peter!” says Wendy. “Peter?”: Mrs Darling vaguely remembers, but remains incredulous. Then Wendy takes out the shadow that Peter had left caught in the window during his last visit and that Wendy must repair before sewing it back on him.

Scene 2 (1st world) “That’s how I spoke about Peter Pan for the first time.”

Wendy, now an elderly lady, is beside her granddaughter Lucy. We understand that everything we have just seen is the story of her memories.

Scene 3a (2nd world) “We’re expected…”

Mr Darling breaks into the bedroom and argues with the two dreamers. He confiscates the shadow and orders Nana, the maid, to burn it immediately. Mrs Darling realises that she is late and leaves hurriedly. Wendy is left alone and starts to cry softly and then goes to her harp and begins to play.

Scene 3b (2nd world) “Help me, Wendy!”

A strange light starts to bathe the bedroom. Behind the stage, we hear the voices of Tinker Bell the fairy and Peter Pan. He begs Wendy to follow him to Neverland. Effectively, his shadow has managed to escape and has gone back; he cannot survive very long without it and Wendy is the only one who can save him. In order to persuade her, he tells her about the marvels awaiting her there. The light becomes brighter and brighter and the window opens violently with the force of the stars. Wendy receives the fairy dust… Nana enters the room and leaves just as quickly, to tell the parents. Too late! When they arrive, Wendy rises up and flies out the window.

Scene 4a (1st world) “I left flying off to the land of Peter Pan.”

Wendy tells the picturesque details of her journey. When the island comes into sight, she sees it as if it were sleeping and waking up as Peter approaches. She observes from above a strange procession gradually setting out.

Scene 5a (3rd world) “Oh ly lya! Oh lyly lya!”

The lost boys are looking for Peter; they are being chased by the pirates; in turn, they are being chased by the Indians; and they are being tracked down by savage beasts (wild cats, wolves and snakes and an enormous crocodile). Everybody goes around the island in that order, faster and faster until…

“They’re going to eat us!”

…the wolves turn round to face the boys. But they make them flee by marching towards them, with their heads between their legs.

Scene 5b (3rd world) “Look! The wolves have led us off course.”

Having been driven off course by the fighting, they find themselves near their hideout, their underground house. They hear Tinker Bell approaching.

As soon as she arrives, she transmits Peter’s order to them: Kill the Wendy bird. The children translate the fairy language (vocalised virtuosos) with difficulty. Finally convinced, they take out their bows and fire into the sky. Wendy crashes onto the stage with an arrow in her chest. Stupor: “ It is not a bird… it’s a lady!” They hide Wendy when they hear Peter Pan coming.

Scene 5c (3rd world) “I see! Is that how you welcome your captain?”

Surprised by their coldness, he announces to them that he has brought them a mother. They move away. Peter is sad then angry. The boys defend themselves and denounce the betrayal of the jealous Tinker Bell, who is still sniggering. Peter banishes her forever and she cries. Suddenly, one of the boys notices that Wendy’s arm has moved. Peter pulls the arrow out; it is stuck into an acorn hanging around the young girl’s neck. “It was my kiss that saved her.”

Scene 6 (1st world) “His kiss saved you? How?”

Granny Wendy explains to Lucy that during one of his visits to her bedroom, she gave Peter a thimble so as not to offend him, because he didn’t know what a kiss was. In exchange, he gave her a kind of acorn that she promised to always keep around her neck.

Scene 7a (3rd world) “She is too weak to move.”

The boys decide to build a cabin around her.

“Go and get me a doctor!”

During the construction, one of the boys, designated as doctor by Peter, pretends to treat the injured girl.

Scene 7b (3rd world) “In my pretty house, there is a door.”

The cabin is finished. In a sweet song, Wendy highlights some things they have forgotten: Door, windows…).

“Lady Wendy”

She agrees to be the mother of all of them and lets them in. Peter stays outside to keep watch. Wendy, saddened by Tinker Bell’s whining, asks for the punishment to be softened.

“Fairies are capricious.”

Peter speaks to her about fairies, about their origin and their habits… Night falls gradually and Peter falls asleep to the sound of the fairies that can be heard far away. The fairies approach and cross the stage.

Scene 8a (1st world) “Did you find his shadow?”

Lucy asks what happened to the shadow. Granny Wendy is uncomfortable, as if she had been caught out (has she forgotten or lied?) and quickly finds an explanation. Her granddaughter is not silly and bombards her with questions to which she replies with growing enthusiasm and tells about the beginning of many adventures. Lucy interrupts her reclaiming her favourite: The mermaids’ lagoon…

Scene 8b (1st and 3rd worlds) The mermaids’ lagoon

The 3rd world is illuminated and shows what the grandmother is describing; mermaids are heard playing in the water with bubbles of light gathered from rainbows. The boys are taking a nap on the rocks. It is the afternoon. Suddenly night falls and the moon rises as if by magic. Two pirates arrive in a dinghy. The 1st world disappears.

Scene 9a (3rd world) “A thousand scurvies!”

Wendy and the boys dive, leaving the rocks upon which Smee and Starkey land with Tiger Lily, the Indian princess; they tie her up and rejoice her approaching death when the tide will have covered her.

Peter then impersonates Hook’s voice perfectly and orders for the Indian girl to be freed. The pirates obey him dumbfounded and the Indian disappears through the water like an eel. Peter, proud of himself, is about to continue his impersonation, when Wendy places her hand over his mouth…

“Hey! Hey! Dinghies!”

We hear Hook’s voice. Surprise! The real Hook arrives swimming and hoists himself onto the reef. He is melancholy.

“Spirit of the lagoon, can you hear me?”

When he inquires about Tiger Lily and discovers what has happened, he invokes the spirit of the lagoon. Peter replies impersonating him, but he is absorbed in the game, finds his real voice and is discovered.

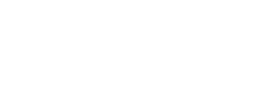

Scene 9b (3rd world) “Peter Pan, the two of us!”

There is a violent fight between the boys and the pirates. Peter confronts Hook who takes him for treachery and wounds him seriously. He is going to finish him off when the crocodile appears unexpectedly with its recognisable tick-tock. Hook is terrified and flees swimming.

Scene 9c (3rd world) The Never Bird

Everything is calm again, a cloud covers the moon, leaving the stage in partial darkness. The pirates have fled leaving their dinghy. Thinking that Peter and Wendy have gone off flying, the lost boys use the dinghy to get back to the shore, Wendy grasps the rocks exhaustedly, but is washed away and drowned by the mermaids, to the sound of their haunting and doleful song. They return, by which time the rocks are almost submerged by the water; they push into the water the nest of a large bird that is hatching its eggs. When the bird flies off to make room, they place the unconscious Peter in the nest and guide it towards the shore.

Scene 10 (1st world) “And how did you manage to escape from drowning?”

Granny Wendy replies to Lucy that the Indians, informed by Tiger Lily arrived just in time to bring her up from the bottom of the lagoon; she awoke with Peter amongst the Redskins. Peter was already recovering very well from his wounds and carrying on in his usual manner during the party that was held to celebrate peace between the boys and the Indians.

Scene 11a (3rd world) “Okanaga Pikani!”

The Indians and the lost boys dance around a fire. Peter is sitting in the middle, next to the chief, Wendy and Tiger Lily. Tinker Bell is sulking in a corner. The Indian chief names Peter “Great white bird.”

“Peter Pan save me. Me very good friend Peter Pan.”

Tiger Lily starts to seduce Peter, to the great dismay of Tinker Bell and Wendy. Under the pretext that it is late and “all” her children must have a bite to eat and go to bed quickly, at Wendy’s demand, Peter runs off in the search of hazelnuts and to ask the crocodile the exact time. Wendy and the boys go down into the underground house, while the Redskins put out the fire and take up places for the watch.

Scene 11b (3rd world) “Come on, boys!”

The boys pretend to be eating around the table, in a racket that their “mummy” tries to calm down; they fight and tell tales…

“What do I hear?”

When Peter arrives, he scolds them, and then plays the role of father. But the game ends up worrying him, because he wants Wendy to be his mother as well.

Scene 11c (3rd world) “Mummy, will you tell us our story?”

When the children are in bed, Wendy accompanies the story with the harp that her “sons” made for singing their own story… not without difficulty, as they interrupt her constantly.

“And this is the most marvellous thing about the story”

When she brings up her happy return to parents impatient for her return, Peter puts a damper on it by telling his own experience: He had also left to have fun in Neverland, but when he returned, the window was closed and his mother was tucking another little boy into his bed; mothers are treacherous, they forget. Wendy gets scared and decides to leave immediately. The boys persuade her to take them with her. While they are all packing their bags, Peter leaves discretely.

Scene 12a (2nd world) “Scissors… Glue… String…”

Mr Darling is working on a model Spanish galleon. Nana passes him the tools on a tray. Mrs Darling is sleeping sitting next to the window, which is wide open. She awakes with a jump and says that she has dreamt that her daughter had returned. The couple argue about their daughter’s disappearance. Mr Darling leaves with his galleon, followed by the maid and her tray.

Scene 12b (2nd world) The bedroom window

Mrs Darling cries, goes to kiss the harp, then sits down and starts to play. She doesn’t see Peter land on the windowsill, listen to her and look at her rapturously. He seems to hesitate… but then pulls himself together, jumps into the room, closes the window from the inside and disappears. Then a halo of light appears next to the window. The music leads us to clearly understand that it is Tinker Bell; the fairies and the stars come to blow on the double window. When it finally opens violently, Mrs Darling jumps and looks at it aghast.

Scene 13a (3rd world) “What? Haven’t you left yet?”

Everybody is sleeping in the underground house, except Wendy. Every so often, the boys turn around in their beds, all at the same time. Peter arrives on tiptoes and is surprised to see that Wendy is still there: She wanted “her children” to sleep a little before the long journey. Peter refuses to leave.

Scene 13b (3rd world) Indian Victory

Suddenly, a terrible noise is heard; the boys wake up with a jump. A battle is being fought above their heads between the Indians and the pirates. The latter are decimated.

Scene 14 (1st world) “Was Hook killed?”

Granny Wendy answers affirmatively to Lucy’s question… then she hesitates and continues. She made a mistake: It was the pirates who decimated the Indians, when they attacked them by surprise. Lucy places in doubt what her grandmother says, who then gets angry and asks how she could have made all of that up! It happened so long ago that her memories are mixed up. Hook had used a trick…

Scene 15a (3rd world) Pirate Victory (correction)

Everything has remained motionless, as if in pause, during the interpolation of the 1st world. The scene resumes backwards and the confrontation resumes with renewed vigour, this time in favour of the pirates; it is carnage. During the battle, we see the children listening from their underground house. Calm returns. Hook signals for silence with his hand and indicates to Smee to sound the drum.

Scene 15b (3rd world) “Hurrah! Indian victory!”

The boys pick up their belongings and go out with Wendy. They are all captured swiftly and silently. Peter suspects nothing and falls asleep crying in his bed. Hook, left alone, descends through one of the secret passages into the house. We cannot climb back out upon arrival and can merely observe angrily as Peter sleeps. A cup of medicine is within reach of his hand; he empties the contents of one of his rings into it and climbs back up, grinning with pleasure.

Scene 15c (3rd world) “Not so fast, I don’t understand a thing.”

Tinker Bell appears in a whirlwind, wakes Peter up and tells him about the capture in a deluge of spoken virtuosos. Before running off to save Wendy, he wants to do something that would make her happy: Drink his medicine, of course. Tinker Bell goes crazy and says that she has heard Hook bragging about having poisoned the contents. Peter doesn’t believe a thing and the little fairy just has enough time to slip between the cup and the boy’s lips to drink it all instead of him.

“So it’s true then. You have drunk it all to save my life.”

She totters and then collapses… she is dying. Peter laments and then thinks: Fairies are born when babies break out laughing; so if the whole world starts laughing, she will be reborn. He urges the public to laugh loudly with him. It is in vain! Tinker Bell murmurs something to him: To prevent her from dying, everybody who dreams of an imaginary land must affirm that they believe in fairies.

“I do believe in fairies”

Peter then encourages the public to sing this profession of faith, followed by the soloists, the choirs and even Lucy and Granny Wendy; the orchestra, subtle at the beginning, ends up covering everything as the fairy awakes. They both fly off to save Wendy.

Scene 16 (1st world) “And so, during all that time, you were a prisoner?”

Lucy impatiently interrupts Granny Wendy, who takes a breath and continues with her story…

Scene 17a (3rd world)

Aboard the Jolly Roger, the atmosphere is very “festive”; the pirates are blind drunk.

“Because I’m a pirate…”

Smee sings about the life of a pirate. They dance and drink with renewed vigour. The chaos is at its peak.

Scene 17c (3rd world) “What’s this rabble of drunken meat?

Hook appears and berates them severely.

“Oh, I’m in good company…”

Left alone, he reflects on his origins and confesses his obsession: Good taste, the art of good manners.

Scene 17d (3rd world) “Are you unwell, Captain?”

Smee asks why Hook is so melancholy, but Hook takes a grip of himself and asks to see the prisoners. He tries to corrupt the boys and enlist them, but Wendy is disgusted by the dirty state of the ship and encourages them to stay on the right side. When Hook prepares to make them walk the plank, the tick-tock of the crocodile is heard. The boys look in the direction of the noise and see Peter climb aboard, carrying an enormous watch with which he knocks out a pirate who charges at him. The tick-tock stops. Peter goes down into the cabin.

“No more tick-tock; it has gone.”

Hook sends several pirates to fetch the whip from the cabin, but they are slain one after the other. Finally, he sends Wendy and the boys… who reappear almost as quickly with Peter and Tinker Bell.

Scene 17e (3rd world) “Shocking! What a lack of manners!”

A terrible battle is fought in which the pirates are exterminated. Hook, driven back along the plank by Peter, asks him to push him with his foot; he obeys. Hook gloats at this lack of manners and ends up in the jaws of an enormous crocodile. As it passes by, the crocodile also swallows the watch that Peter had borrowed from him and goes tick-tock once again.

Scene 17f (3rd world) “You were grandiose; real heroes of the seas.”

Wendy congratulates everybody for the victory, but then becomes disillusioned when she hears Peter ordering the boys to throw all the bodies into the sea and to dress themselves in the pirates clothing. He asks for “his” things to be brought to him: They bring him the captain’s hat, jacket and cigar case. Wendy is dumbfounded when she sees Peter plant himself before her haughtily; he adopts a worried look and curls up his index finger in the shape of a hook. Finally, when the boys start singing the pirates’ drinking songs, she realises that they can no longer see her and she runs to the cabin covering her ears.

Scene 18 (3rd to 1st world)

The orchestral transmission enables the progressive passage to the musical setting of the first scene of the opera.

Wendy is lying down in her bedroom, like at the beginning, with her hands over her ears. Her parents’ argument is heard in the background. A violent noise awakes her; she sits up on the bed, a little sad.

Scene 19 (1st world) “But I know that it wasn’t a dream…”

“There you are! I experienced the most beautiful moments of my life and it was just a dream,” says Granny Wendy. Lucy protests and as her grandmother looks at her taken aback, she goes to the back of the room to find Peter’s shadow. Wendy is deeply moved, takes the shadow and kisses it. The light becomes more and more intense, lighting up the stage and the public while Lucy withdraws and disappears. When the orchestra announces the arrival of Peter Pan, Wendy cries his name: “Peter!”

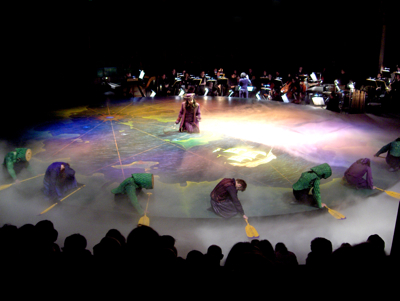

Pictures of the 2006 production

(Back to top)

PETER PAN or the real story of Wendy Moira Angela Darling

Production of Théâtre du Châtelet – May, june 2006

(Credits : Isabelle Partiot)

Arrival to Neverland : Island comes into sight “It appeared to be waking up…” (scene 4b)

The parade (Wildcat, wolves crocodile) : (scene 5a)

The lost children : “They will eat us” (scene 5a)

Tin-Tam’s arrival : “Listen to her bells !” (scene 5b)

“Tin-Tam ! Tin-Tam !“ (scene 5b)

“Kill the Wendy bird !” (scene 5b)

Peter Pan : “Who fired ?“ (scene 5c)

The mermaid’s lagoon (scene 8b)

Lost children, Wendy, Peter : “The pirates ! Quick, dive !“ (scene 9a)

The mermaids place the unconscious Peter in Never Bird’s nest : (scene 9c)

Indiens, Lys Tigré : “Okanaga !“ (scene 11a)

Lost children, Wendy, Peter, Indiens asleep, as well as Mrs Darling asleep in 2d world (scene 11c)

“Mummy, will you tell us our story ?“

Mr Darling, Nanita, Mrs Darling : “Oh ! I dreamt that my little girl had come home” (scene 12a)

Lucy, Hook, Granny Wendy : “A spear straight through the heart !” (scene 14)

Lost children, Wendy, Peter in the underground house, watched by pirates (scene 15a)

“We can’t hear anything”

Tin-Tam’ death (scene 15c)

Sails of the pirate’s ship “Jolly Roger”

Hook : “Good manners …” (scene 17c)

Final fight : “Why kill me ?” (scene 17e)

Granny Wendy and the white shadow : “Peter !” (scene 19b)

Interview du compositeur par Rémy Louis

Les trois mondes de Peter Pan

Après le théâtre et le célèbre dessin animé, l’histoire de James Matthew Barie est aujourd’hui devenue une œuvre lyrique grâce au compositeur Patrick Burgan. Commande du Théâtre du Châtelet, Peter Pan, interprété par des chanteurs enfants et adultes, sera créé en mai au Théâtre Zingaro sous la direction de Claire Gibault.

Chacun croit connaître l’histoire de Peter Pan. Pourtant, vous avez donné à votre fantaisie lyrique un sous-titre : « … ou la véritable histoire de Wendy Moira Angela Darling ». Pourquoi cela ? À mes yeux, le sous-titre enrichit la carte d’identité de l’œuvre. En l’occurrence, il dévoile une autre dimension de Peter Pan, plus énigmatique, présente dans le conte originel de James Matthew Barrie. J’ai aussi voulu en accentuer l’aspect « éternel retour » en organisant l’action comme un flash-back permanent.

Votre livret développe trois « mondes » simultanés et interactifs. À quoi correspondent-ils, et quelle est leur fonction ? Le premier correspond à la réalité du moment : devenue grand-mère, Wendy raconte sa vie à sa petite-fille Lucie. Le deuxième matérialise son enfance, les souvenirs (non sans déformations) de ses souffrances lors des disputes de ses parents, M. et Mme Darling. Le troisième est bien sûr cet ailleurs où Peter Pan l’a entraînée. Le spectateur est donc amené à effectuer de fréquents allers-retours entre ces mondes, de manière quasi cinématographique. Mon choix de centrer l’opéra sur Wendy, en renonçant par exemple aux personnages secondaires des frères, ne résulte qu’en partie des contingences scéniques, qui obligent à réduire certains éléments et à en amplifier d’autres. De même, ce ne sont pas des raisons d’économie qui ont conduit Barrie à demander que Crochet et le père de Wendy soient incarnés par le même acteur.

… ce qui a été le cas à la création en 1904 à Londres, mais aussi dans les deux célèbres plays de Broadway de 1950 et 1954, où Boris Karloff et Cyril Ritchard assumaient chacun les deux personnages. Oui, et j’ai même développé cette idée en faisant incarner la fée Clochette et la mère de Wendy par la même personne. Ainsi, dans le troisième monde, Wendy retrouve ses deux parents… et son frère décédé, qui n’est autre que Peter Pan. C’est la part fortement autobiographique du conte. Le frère aîné de Barrie est mort à treize ans – l’âge de Peter – quand lui-même en avait sept. L’aîné était le préféré de sa mère, et sa mort l’a rendue à moitié folle. Barrie aurait voulu être aimé par elle de la même façon. Mais il a compris qu’il ne pourrait jamais lutter avec ce « rival » éternellement jeune, qui ne grandirait plus. L’opéra donne ces clés petit à petit, en révélant que Wendy avait un frère. La petite fille quitte le deuxième monde quand Peter Pan vient la chercher ; plusieurs lectures sont possibles, car Peter l’appelle un peu comme le clair de lune séducteur et maléfique vous attire et vous perd. J’ai organisé ces éléments pour qu’ils puissent être compris au premier degré par de jeunes enfants, tandis que des spectateurs plus âgés les apprécieront à un autre niveau.

L’adaptation merveilleuse, à tous les sens du terme, de Walt Disney a donc simplifié le personnage, et ôté au conte des soubassements importants ? Cette adaptation a gommé une dimension surréaliste très « début de siècle », une part de non sense typiquement britannique, et aussi un certain impact physique de la frayeur. Peter Pan est devenu un gavroche malicieux et adorable, alors que celui de Barrie est dérangeant, égocentrique, dangereux, allant jusqu’à supprimer les enfants perdus qui prennent la liberté de grandir : il est difficile de s’identifier à lui ! Cette simplification s’imposait à Disney pour qu’il puisse recréer son propre univers. Pour ma part, j’ai réintroduit l’inquiétude, et un véritable sentiment de crainte quand, à la fin, Peter Pan et les enfants perdus deviennent les pirates. Wendy crie, elle court en se bouchant les oreilles… et, par un effet de fondu enchaîné, se retrouve dans sa chambre, avec ses parents qui se disputent à côté. C’est un exemple de ces allers-retours qui installent une ambiguïté entre rêve et réalité.

Est-ce pour vous une manière de terminer, en un sens, ce que Barrie n’avait peut-être que suggéré ? Certainement. Dans l’opéra, Peter déploie une énergie enivrante. La transformation de la fin suggère que la beauté et la jeunesse ne sont pas seulement ce que l’on croit. En tuant Crochet et en reprenant ses attributs les plus voyants, il tue son père, et en même temps prend sa place.

Les trois niveaux s’imbriquent donc sans cesse. Comment parvenir à les différencier, alors que la scène induit par elle-même unité de temps et de lieu ? Sur scène, quand un personnage parle, il le fait comme vous et moi. Quand il chante, il est ailleurs, et vous avec. Ainsi, dans l’opéra, la réalité parle, et le rêve chante. Le monde de Wendy âgée et de Lucie est exclusivement parlé, sans musique – ce sera Marie-Christine Barrault qui incarnera cette Wendy. La musique ne se glisse sous leurs voix que pour annoncer le passage à un autre monde. Le deuxième, qui évoque ce qui est inscrit dans le souvenir de Wendy grand-mère, recourt à la technique du mélodrame : les voix sont parlées, mais avec une musique qui demeure présente et les enserre dans les portées. Ces rôles seront tenus par les chanteurs, qui seront aussi présents dans le troisième monde, où ils interviendront alors exclusivement en voix chantées. J’ai tenu à auditionner les acteurs-chanteurs des deuxième et troisième mondes. Car il n’est pas toujours facile, pour un chanteur, de déplacer sa voix – littéralement parlant.

Ce dispositif impose une très grande précision dans le réglage des passages d’un monde à l’autre. Avez-vous composé quelques interludes orchestraux pour les faciliter ? Quand ils existent, ils sont brefs. Une scène peut s’interrompre brutalement. Crochet est tué dans la bataille entre les indiens et les pirates Tout se fige, exactement comme un arrêt sur image. Dans un coin, Lucie s’écrie : « Crochet a été tué !? » Wendy âgée confirme, puis se ravise, ce qui fait douter Lucie. La musique revient alors en arrière, en contrepoint inversé…. Quand j’ai évoqué le projet avec la metteur en scène Isabelle Partiot, je ne lui ai pas caché mes idées assez extravagantes. Valait-il mieux y renoncer tout de suite ? Elle m’a répondu qu’elle se chargerait de trouver les solutions. Mais certains moments, évidents au cinéma, seront plus délicats à réaliser sur scène.

La Wendy âgée et la Lucie du premier monde restent toujours sur scène, je suppose ? Et – pardonnez cette résurgence disneyenne immédiate ! –, est-ce que Peter Pan vole ? Le premier point relève du choix du metteur en scène, même si je pense que les deux personnages ne doivent en effet jamais s’absenter, quitte à être parfois masqués. Pour le vol… je ne sais pas encore comment Isabelle fera ! (l’entretien a eu lieu en février, Ndlr). Des acrobates de l’École du cirque ont été engagés pour les nombreuses scènes de batailles du troisième monde qui, pour être réalistes et spectaculaires, doivent bouger dans tous les sens. Mais pour éviter l’impression d’un fouillis, Isabelle a choisi de représenter chaque entité – enfants perdus, pirates, indiens… – par des groupes de quatre à cinq personnes. Les chœurs, de trois fois deux cent trente enfants en alternance, n’interviennent que dans le troisième monde, et resteront sur des gradins. Même le célèbre crocodile est, musicalement, incarné par un chœur. Isabelle a eu l’idée magnifique de faire un décor humain. La maison souterraine, les arbres… seront matérialisés par les acrobates. Le plus difficile à gérer sera la multiplicité des changements à vue, mais en même temps, toutes ces contraintes sont stimulantes.

La présence d’un important chœur d’enfants est évidemment une donnée de base de tout le projet ? Absolument. Il fait suite à mes Chants de Thémis, écrits en 2000 pour Toni Ramon et la Maîtrise de Radio France, les chorales des lycées et collèges de l’Académie de Paris, et l’ensemble Percussions-claviers de Lyon. Un projet initié par Jeanine Delahaye, inspectrice de la musique à l’Académie de Paris, qui souhaitait confronter des professionnels à de véritables amateurs. Ce succès a rencontré mon lointain désir d’écrire un opéra autour du personnage de Barrie. L’idée a plu à Jean-Pierre Brossmann, et son engagement a permis de réunir les moyens considérables qu’exige l’opéra.

À propos de moyens, quelle formation orchestrale avez-vous retenu ? L’opéra durant un peu plus de deux heures, j’avais besoin de couleurs bien différenciées. L’action, le spectacle doivent captiver, rebondir, tout en restant compréhensibles. À la formation Mozart usuelle, j’ai ajouté harpe, piano, célesta, plus trombones et tuba, ces derniers créant du volume pour l’arrivée de Crochet. L’orchestre comporte quarante musiciens, sans trop de cordes, car le Théâtre Zingaro a ses propres exigences de lieu. L’orchestre occupera environ le tiers de la scène. Qu’il ne couvre pas les chanteurs est mon problème de compositeur, pas celui de l’effectif ! La musique constitue un personnage situé à l’intérieur de l’action, comme dans les opéras de Wagner.

Mais comment concilier une certaine simplicité de l’écriture, en partie conçue pour des amateurs, avec la complexité scénique des événements ? Écrire « simple » est un très bon exercice, parce que c’est toujours difficile ! Je ne voulais pas faire de concessions à mon langage musical, c’est-à-dire que la simplicité se voie ou s’entende trop. La complexité apparente de la musique n’en est pas une, pratiquement, pour les chanteurs. Le compositeur doit toujours veiller à simplifier la vie de l’interprète, qui a ses propres difficultés à résoudre. Si je me suis « lâché » pour les personnages de Peter Pan et de Wendy enfant, chantés par des solistes de l’ensemble Sotto Voce, j’ai dû rester très vigilant pour l’émission vocale, les tessitures, et la complexité rythmique de l’écriture pour les chœurs.

Quelles sont les tessitures des chanteurs, qui mêlent adultes et enfants ? Soprano colorature pour la mère de Wendy / la fée Clochette, baryton-basse pour le père / Crochet, ténor léger pour la servante Nanita / Simoun, basse pour le chef indien. Ce sont les seuls chanteurs adultes de la distribution. S’y ajoutent sept rôles solistes chantés par des enfants (dont ceux, très exigeants, de Wendy et Peter Pan), celui de Lys tigré et ceux de quatre enfants perdus auxquels j’ai donné un profil caractérisé, en usant de ressorts comiques. Par exemple, le fanfaron de la bande, celui qui sait tout, est aussi le plus petit… Et bien sûr, en définitive, il ne sait rien !

Tel que vous le décrivez, il a un petit côté Joe Dalton ! (Il rit.) C’est presque ça, en moins capricieux et obsessionnel, tout de même ! Remarquez, l’un des trois autres n’est pas loin d’évoquer Averell. J’ai cherché à recréer ces basculements où l’on glisse dans la satire, en renforçant à la fois le sentiment d’inquiétude et le sentiment comique, comme dans le cinéma italien d’un Dino Risi.

Cette caractérisation induit-elle des thèmes musicaux spécifiques, ou une évolution permanente liée à l’action scénique ? Les deux en même temps ! L’appartenance conditionne les thèmes : la mère / la fée Clochette, le père / Crochet, etc. Les scènes de batailles sont entièrement régies par les thèmes et les carrures musicales. Une cellule rythmique, « Pe – ter Pann » – une brève, une longue, une plus longue encore –, parcourt l’opéra et en articule la forme. Pour composer, je choisis et peaufine mes thèmes, avant d’en tirer le canevas définitif. Je n’ai commencé à écrire que lorsque j’ai senti que les thèmes étaient sûrs, suffisamment solides pour en déduire tout le développement orchestral.

Une question pour conclure : pensez-vous appartenir à une école esthétique particulière : post-sérielle, néotonale ou autre ? Je suis dans l’Empire du Milieu ! Un compositeur dispose de tous les moyens que le passé, même très récent, lui a donnés. J’espère évidemment avoir un style musical reconnaissable. Mais c’est le geste musical qui fonde l’originalité et la personnalité : que vous utilisiez la série dodécaphonique – un outil utile pour gérer le mode chromatique sur le plan thématique et contrapuntique – ou un mode pentaphonique, c’est l’ambiance et la couleur musicale recherchées qui priment. L’unité stylistique sera présente, au-delà des techniques utilisées, parce que le geste reste le même.

Propos recueillis par Rémy Louis

Février 2006

Note d’Isabelle Partiot-Pieri (Mise en scène, décors, costumes accessoirisés des acrobates)

(retour en haut de la notice)

Peter Pan dans le cercle magique du cirque. Bien plus qu’une histoire pour enfants, « Peter Pan » est une étonnante parabole sur l’existence et sur la mort, selon Patrick Burgan. Du quotidien douloureux au foisonnement du monde imaginaire, Isabelle Partiot met en scène ce voyage poétique entre rêve et réalité.

Le premier monde dans lequel se situe « Peter Pan » est celui d’aujourd’hui. En racontant sa vie à sa petite-fille Lucie, Wendy s’adresse, à travers elle, à l’ensemble des spectateurs. Elle évoluera donc au milieu du public, dans un rond de lumière, habillée comme de nos jours. Lucie l’écoute et pose des questions auxquelles sa grand-mère répond tout en amenant le public des gradins vers la scène (en)chantée.

L’entrée dans le deuxième monde nous plonge quelques années en arrière, à Londres. L’orchestre s’infiltre progressivement entre les dialogues, pour suggérer la réminiscence d’un l’univers triste et étriqué : celui des années 50. Durant ces années maudites et malheureuses, Wendy, enfant, tente d’échapper à la pesanteur de l’atmosphère familiale et s’envole, retrouvant alors Peter Pan, la métaphore du frère mort, jeune pour l’éternité.

Nous glissons alors dans le troisième monde, fait de couleurs et de musique : le monde rêvé. Le père de Wendy devient l’inquiétant Crochet, sa mère la jalouse Tin-Tam, tandis que la gouvernante se transforme en pirate ambigu aux ordres du noir Capitaine. Grinçantes images travesties de ses proches, ces figures, étrangement familières et déformées comme dans un cauchemar, harcèlent Wendy. Après s’être retrouvée au sein des enfants perdus, elle est devenue leur mère à tous et la compagne de Peter, à la fois protectrice et complice de ses bizarreries. Peter, lui, n’est qu’imagination, imprévisibilité, fluidité, inconstance. Il a l’apparente incohérence des rêves, leur légèreté, leur brusque changement de couleurs. Il est le rêve. Tout autour de lui grouillent des créatures burlesques, sauvages, trépidantes, animales. Enfants perdus, fauves, pirates, sirènes, peaux-rouges, fées, loups et oiseaux s’entremêlent dans le foisonnement du pays imaginaire, qui est à la fois île, cabane, lagon, maison souterraine, campement indien et bateau de flibustiers.

Danses, luttes et rythmes sauvages alternent alors avec des plages de poésie extatique – « liquide », selon le compositeur –, qui s’estompent parfois pour revenir à l’univers gris de la chambre d’enfant de Wendy ou au savoureux talent de conteuse de Mamie Wendy.

Inscrire dans le cercle magique du cirque et dans un lieu unique ces débordements débridés – en apparence seulement ! – de temps, de lieu et d’action ; saisir d’un trait de pinceau la silhouette de Peter Pan en s’appuyant sur son image diffractée en trois fois deux cent trente enfants complices, doubles oniriques comme sortis d’un miroir à facettes : enfants-jungle, enfants-végétaux, rois de l’imaginaire… ; raconter enfin une histoire multiple, jonglant entre évocation et réalité pour laisser ouverte la question : « ai-je rêvé ? » : telles sont les données poétiques de cette œuvre ouverte, qui offre à un metteur en scène tout un monde de possibilités.

Isabelle Partiot, metteur en scène.

15 janvier 2006

World premiere’s casting and specifications of the Stage director about her options

Actors (1 adult, 1 kid**) :

Granny Wendy (speaking role) : Marie-Christine Barrault

Lucy (speaking role, ca.10 years old) : Clara Le Corre / Romane Gorce*

Soloist kid singers** (7 roles) :

Peter Pan (child voice, ca. 12 years old) : Mathieu Leroux / Théo Bourgery*

Wendy young girl (soprano, ca. 15 years old) : Pauline Lazayres / Alison Holm*

Guignard, lost boy (child voice, ca. 12 y. o.) : Anton Barsoff/ Timothée Gery*

Zigomo, lost boy (child voice, ca. 12 y. o.) : Sixtine Le Borgne / Raphaël Triquet*

Frisé, lost boy (child voice, ca. 12 y. o.) : Juliette Montagne / Bastien Robinet*

Flocon, lost boy (child voice, ca. 12 y. o.) : Louis Pottier-Arniaud / Malory Matignon*

Lys Tigré, indian chief’s daughter (mezzo-soprano, ca. 16 y. o.) : Anaïs Gonzalez / Charlotte Taïeb*

Soloist adult singers (4 adult roles + 1 = 5) :

Mrs Darling (speaking role) – Tin-Tam (soprano coloratura) : Gaële le Roi

Mr Darling (speaking role) – Captain Hook (bass-baritone) : Marc Barrard

Nanita, nanny (speaking role, drag part) – Simoun, pirate (light tenor) : François Piolino

Teigne, pirate – Indian chief (bass) : Eric Freulon

Lost children supporting role (soprano) : Isabelle Poinloup****

Choirs (children choirs from Paris schools, Choirs of Châtelet, Maîtrise de Paris***, all standing in the tier behind the orchestra)

Pirates : male choir

Mermaids : female choir

Indian warriors : male choir

Indian women : female choir

Indian kids : children’s choir

Boys (the lost children) : children’s choir

Fairies : children’s choir and female choir

Wildcats, snakes, wolves, crocodile : children’s choir

11 acrobats and 4 extras : Circus artists from Charles Millet’s Compagnie du Bois Midi****

NB : To make the action and the different locations of the story understandable, I have added on stage 11 acrobats and 4 extras, who “ARE” the set with “prop-costumes”, and act too as soloists do.

They play alternately : pirates, indians, crocodile, wildcats, wolves, mermaids, fairies, rowers, barrels, sails, trees, door and windows plus chimney, harp, …, with quick changes for their “prop-costumes”

- All roles and choirs, according to Patrick Burgan, can be sung by adults.

*Every child role is double-cast

**Children’s choir Sotto Voce (Scott Alan Prouty, director)

***Maîtrise de Paris (Patrick Marco, director)

****Participants not originally in the score added by the director, according to the composer and the conductor (writing in italics)